Did you give to Comic Relief this year? I’m guessing that if you did, it was probably done either with the notion that “giving is good”, or possibly: “I give every year, it would not feel right to skimp just because I’m bored with CR, and/or ________ (insert compassion-fatigue excuse).

Did you give to Comic Relief this year? I’m guessing that if you did, it was probably done either with the notion that “giving is good”, or possibly: “I give every year, it would not feel right to skimp just because I’m bored with CR, and/or ________ (insert compassion-fatigue excuse).If not that, then maybe: "I give because compared to so many people in the world I'm relatively well-off."

Or: "Giving makes me feel more serene, gratified, even joyful."

So which of these options get the Buddha thumbs-up?

Well, suprisingly, if we’re going by the Dana Sutta (AN 7.49), all of them land you a “returner” status, which in modern parlance pretty much translates as Epic Karma Fail. The karma Trump card is: we give because “this is is an ornament for the mind, a support for the mind”.

In other words giving, in and of itself is a practice, and a practice quite distinct from all those heartstring-tugging VTs (it was the the slightly wild-eyed and unshaven David Tennant in a hospital in Uganda that finally got me reaching for my mobile phone to "text a fiver"). As a man dependent on alms, the Buddha would have recognised that if alms-giving was predicated on feeling compassionate, then those times our hearts feel squeezed and parsimonious, he and his monks wouldn't eat.

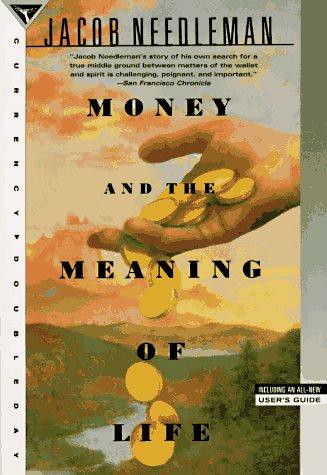

The “ornament” and “support” argument for giving (though not presented exactly in these terms) is something that came up recently in Martin Aylward’s Work, Sex, Money, Dharma retreat. Perhaps because I found myself mentally wrestling with the argument on retreat, I have subsequently been reading Jacob Needleman’s Money and The Meaning of Life, a book which I think fleshes out some of the bones of the Dana Sutta.

Needleman’s thesis is that although we tend to see ourselves as obsessed with money, in some sense we don’t take it seriously enough, because we fail to see how money can be used as a means to understand ourselves better (i.e. as an ornament and support for the mind).

He begins by showing how the earliest coins bore a religious symbol on the one side (God) and a secular symbol on the other (Caesar), acting thus as an instrument for human interactions in the material world, while helping us to remember our dependence on moral laws, the dharma, in buddhist terms.

“The ethical laws governing money exchange connected this activity vertically to the divine commandments; and the nature of money payment in itself was testimony to the horizontal, material dependence of human beings upon each other” (p.60).

The fact that we no longer make this link alienates us, he believes, from the true "meaning" of money: a facilitator for our spiritual and material desires.

If money is the outward manifestation of the human ego, dictating how we deal with all matters material, intellectual, and emotional, then by paying more conscious attention to it (mindfulness), gives the mind greater space and ease in its dealings with money - a taste of anatta. In the process, we also perhaps get greater access to the boundless “wealth” of conscious life, real understanding of ourselves in the midst of work, relationships, and our financial dealings.

Money, he argues is is good at solving problems, but bad at opening questions. Used wrongly, it “converts inner questions that should be lived into problems to be solved”. Needleman’s book opens all sorts of questions which bear further exploration. It is a lovely, warm volume, written at time like a campus novel, at other times like a history of ideas; boldly argued, and studded with arresting insights.

No comments:

Post a Comment